This is Part 4 of The Real Cost of Agentic AI series.

Summary

As AI “agents” become part of the workforce (think Copilot acting like a digital employee), Microsoft’s licensing strategy may evolve to treat these agents as licensable entities. This post discusses the concept of per-agent licensing – the idea that each AI agent might carry its own licensing cost or requirements – and examines early signs of this in Microsoft’s offerings. What happens when your company has dozens of AI bots? Will each require a license just like a human employee would?

What’s happening

Microsoft’s marketing often portrays Copilot and similar AI as “a new team member” or “virtual colleague.” It’s more than a metaphor – in some scenarios, these AI agents are effectively taking on work like an employee. With that shift comes a provocative question: Are we going to license AI agents the way we license people? Some folks have started asking whether digital workers will eventually have a Microsoft licensing package similar to human workers.

We’re already seeing hints of this. For instance, Microsoft recently introduced Microsoft 365 Copilot for Service, a role-based Copilot agent for customer service scenarios. If you want to deploy that “service agent” in your organization, it’s not covered by the standard Copilot license alone – Microsoft prices it at an additional $20 per user per month for those who already have M365 Copilot. In effect, if your support rep is aided by a specialized AI agent, you’re paying extra for that agent’s capabilities, bumping the cost of that “employee+agent duo” from $30 to $50 per month.

This is a per-user, per-agent add-on model, albeit framed as a single $50 license that includes both the base Copilot and the service agent. We can imagine this pattern repeating: today it’s a service agent, tomorrow it could be a sales Copilot agent, a finance Copilot agent, etc., each as a separate licensing component.

Additionally, Copilot Studio lets organizations create custom AI agents. Currently, Microsoft’s approach is to charge per message (consumption) for those agents, rather than a flat fee per agent. However, they did require a minimum spend (message pack) originally – effectively a baseline cost for having an agent running in production. Jukka noted that Microsoft removed a $200/month minimum commitment for Copilot Studio by introducing pure pay-as-you-go in late 2024, which shows they are still feeling out the model. But one interpretation is that Microsoft initially expected customers to pay for AI agents much like a subscription (even if usage was low), and only later adjusted to lower the entry barrier.

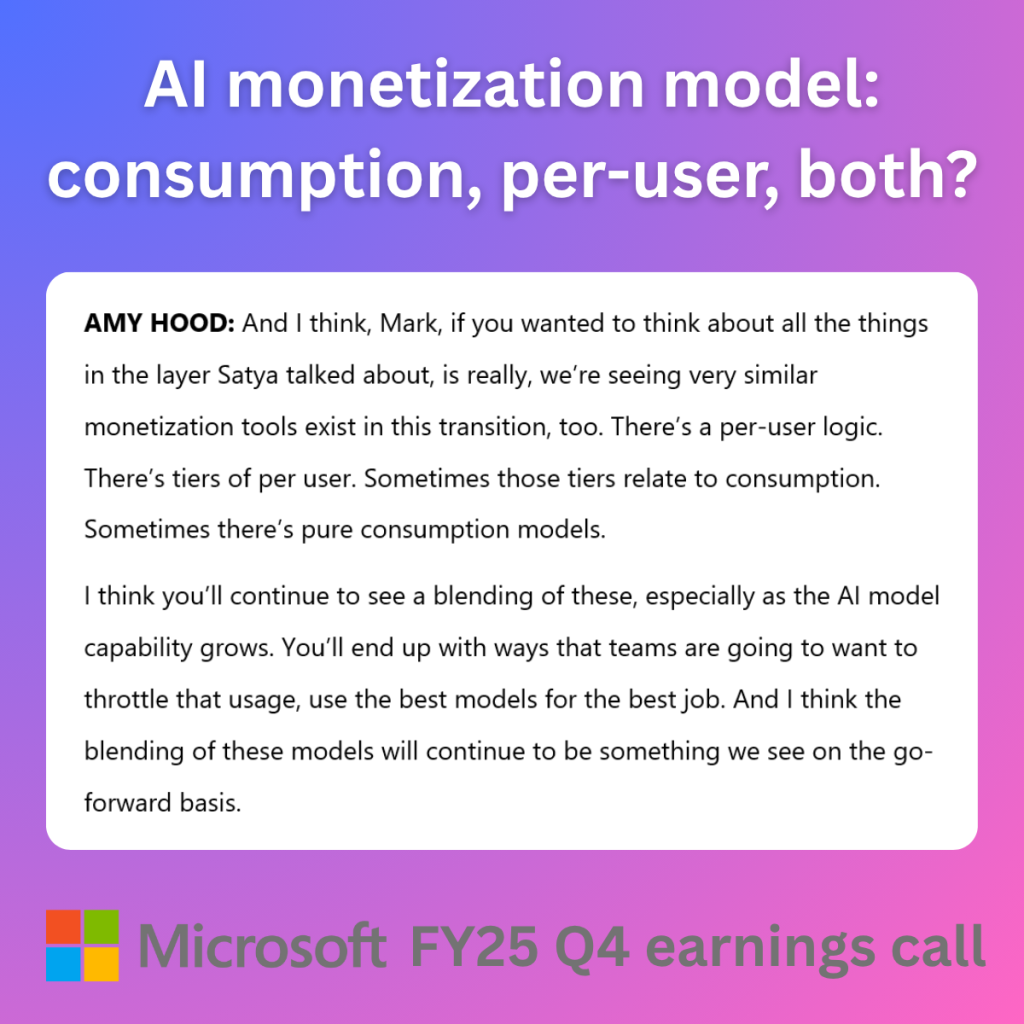

While all eyes are on the Azure style consumption model today, in the FY25 Q4 earnings call there was a comment from Microsoft CFO Amy Hood that specficially addressed this topic. “There’s a per-user logic. There’s tiers of per user. Sometimes those tiers relate to consumption. Sometimes there’s pure consumption models.”

Why it matters

The prospect of per-agent licensing raises both financial and strategic considerations. Financially, organizations might end up budgeting for “digital headcount.” For example, imagine a company that deploys 10 custom Copilot agents (one for HR inquiries, one for IT support, one for sales forecasting, etc.). If each of those in the future required some licensing fee – whether as a fixed monthly cost or a dedicated pool of consumption – the costs could add up quickly.

It changes the cloud cost discussion: you’re not just counting user seats, you’re counting AI agent seats. This matters because it could dampen enthusiasm for creating many specialized agents. Companies might consolidate needs into fewer agents to avoid multiplying costs, potentially limiting the granularity of solutions.

Strategically, if Microsoft indeed heads toward per-agent charges, it could influence how AI solutions are designed. Maybe instead of ten narrow agents, you build one broader agent to cover multiple functions, to keep licensing simple – but that might be less effective. It also matters for competitive positioning: if Microsoft charges per agent and a competitor offers an unlimited number of agents for one price, that could sway decisions.

From a governance angle, tracking which agents exist and ensuring each is properly licensed could become a new responsibility (today we manage user licenses; tomorrow, also “agent licenses”?). There’s also an aspect of fairness or optics: if an AI does the work of 5 people, does paying one license fee make sense, or should you pay 5? Microsoft might argue the value of an agent is tied to how much it’s used, which circles back to consumption pricing – but if they ever enforce a per-agent fee, organizations will want to ensure those agents are truly pulling their weight.

Another reason this matters is predictability and compliance. If an AI agent can initiate actions across your tenant, could its “presence” inadvertently require licenses for other things? For instance, if a Copilot agent accesses a Dynamics 365 environment, does that agent need a D365 license or is it covered by the user’s license? These edge cases could proliferate. We already know that if a process (bot) accesses a system on behalf of users, Microsoft has rules (multiplexing, etc.) requiring proper licensing for the underlying systems.

An agent might trigger similar requirements: i.e. a digital worker still needs all the same access rights (and thus licenses) a human would if it’s pulling data from various Microsoft services. So, the significance is not just paying for the agent itself, but ensuring compliance across the board when agents operate.

Lastly, psychologically, treating AI as licenseable users is a new paradigm for customers. It could influence how they value AI contributions – maybe by comparing cost vs output just like an employee’s salary vs productivity. This could actually be helpful in justifying AI: e.g. “Our $50/month AI agent resolves as many tickets as a tier-1 support rep might – a good ROI.” But it could also lead to pushback: “We’re not paying Microsoft for yet another seat just because we enabled a bot.”

In summary, if digital employees come with digital licensing, it matters because it will shape investment decisions, architectural choices, and the overall calculus of AI in the workplace.

My perspective

I find the notion of per-agent licensing both logical and a bit dystopian – logical because, of course, Microsoft will seek to monetize whatever delivers value, and if an AI agent is doing work, there’s revenue to be captured. Dystopian because it raises the surreal scenario of “Every employee gets an AI assistant…but you have to license that assistant separately.”

In my view, Microsoft is already testing the waters. The Copilot for Service $20 add-on is a prime example: it sets a precedent that certain agents = extra fee. I suspect we’ll see more of these vertical/functional Copilots. My somewhat contrarian stance is that Microsoft might eventually bundle a certain number of generic AI agents into higher-tier plans, but as soon as you want specialized or additional ones, you’ll pay per agent. It’s akin to how some subscriptions might say “includes up to 5 bots” and beyond that you buy more.

As someone who has worked through countless Microsoft licensing guides, I can already envision the fine print. My take is: prepare for this. If you’re designing solutions, keep an inventory of your AI agents and their scope. Even if today they’re “free” aside from usage, tomorrow there might be a switch. It’s not unprecedented – years ago, workflow automations were unlimited until one day Microsoft said “now there are capacity limits, buy add-ons”.

The agents we happily create now could be counted later. In practical terms, I advise clients to treat each meaningful AI agent as you would a new application or a hire: justify its existence with a business case. That way, if Microsoft slaps a price tag on it, you can decide if it’s still worth it.

On the flip side, I’m actually optimistic that if we prove value, paying for agents won’t be a hard pill to swallow – the ROI might be obvious (e.g. an agent that saves 100 hours of work might be easily worth a license fee). As an advisor, I’m already exploring how to quantify the benefit of each agent so that decisions around them can be made rationally.

Also, let’s not forget the consumption vs flat fee dynamic: I’d prefer Microsoft stick to charging by usage (messages) rather than a flat per-agent fee, because at least usage scales with value delivered. A dormant agent costing money would be the worst-case scenario. I will be voicing this perspective in the community: if “digital employees” must be licensed, let it be in a way that correlates with their output.

In conclusion, I anticipate per-agent licensing becoming a reality in some form. My take is to stay ahead of it – manage your stable of AI bots wisely and keep an eye on licensing announcements. And, as always, read the fine print; if an upcoming licensing guide hints that, say, more than N agents requires a new SKU, you’ll want to know before it impacts your budget. (This is where having a licensing expert on call comes in handy – we keep track of these developments so you can focus on using the tech.)